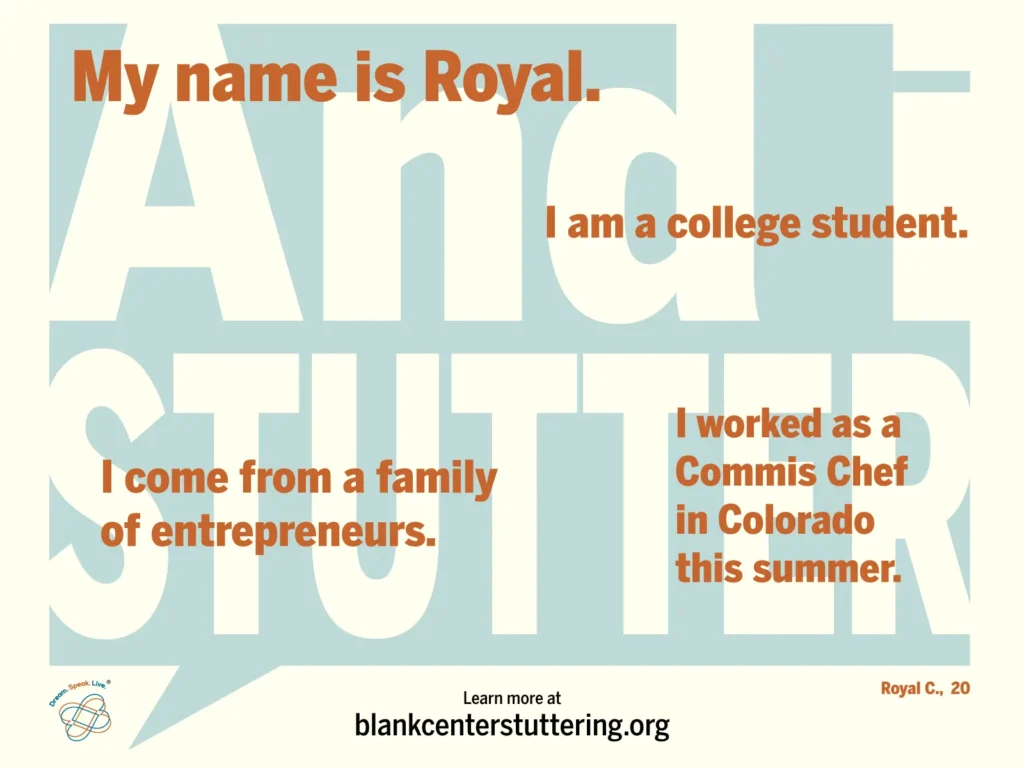

My name is Royal Cumby, I am 20 years old, and I am a person who stutters. I started going to speech therapy in my local school district when I was three years old; and for over fifteen years I have had six school speech therapists; yet my stutter had not gone away.

In therapy, the focus was on achieving fluency. Although my school speech-language pathologists (SLPs) never explicitly told me that fluency was the only way to communicate effectively or succeed socially, I knew that this is what they were thinking. They taught me various strategies aimed at minimizing my stuttering, but for me, stuttering is a natural part of my speech. It often felt like they were asking me not to talk at all.

This pressure to meet an unrealistic goal left me feeling critical of myself, deeply disappointed, and made me question my self-worth because of my stutter.

My parents were watching TV when they saw an advertisement for the Lang Stuttering Institute at UT Austin, now known as the Arthur M. Blank Center for Stuttering Education and Research. I attended my first Dream. Speak. Live. camp when I was twelve, and it changed my life. At the center, the focus was on becoming an effective communicator while embracing my stutter. For the first time I learned what self-disclosing is, which is simply saying that I am a person who stutters. This simple thing not only makes you and the audience comfortable with your stutter, but it also creates space within the conversation for the person who stutters.

For the first time, I heard that stuttering is okay; this was the first time in 12 years that I felt like my way of speaking was accepted.

Before attending camp, I avoided giving presentations or speeches in school, my SLPs even spoke to my teachers, requesting that I be allowed to present one-on-one or not at all. This created a fear of public speaking and reinforced the belief that my natural way of speaking was unacceptable. However, participating in public speaking as a person who stutters has been empowering. It helps to normalize stuttering and demonstrates that even in moments of disfluency, a person can still deliver a message and be an effective communicator.

Every Dream. Speak. Live. camp has a waitlist, and I was fortunate to be selected to attend. If I had not been chosen, I can confidently say that I wouldn’t be nearly as confident as I am today. I wouldn’t have the quality of life I enjoy now; I would struggle to participate in social activities, avoid public speaking, and would feel upset and frustrated with my stutter. Most people who stutter get treatment in schools, but in my case this treatment was not effective, and it was harmful. If we can get the methods and research of the Blank Center in schools, kids who stutter will receive effective and life changing treatment.